This is the first in a series of notes about research into The Hero Story. I’m taking these notes as I seek to explore connections between Joseph Campbell, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, Jesus and Batman.

Notes

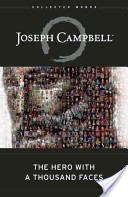

Whether we listen with aloof amusement to the dreamlike mumbo jumbo of some red-eyed witch doctor of the Congo, or read with cultivated rapture thin translations from the sonnets of the mystic Lao-tse; now and again crack the hard nutshell of an argument of Aquinas, or catch suddenly the shining meaning of a bizarre Eskimo fairy tale: it will be always the one, shape-shifting yet marvelously constant story that we find, together with a challengingly persistent suggestion of more remaining to be experienced than will ever be known or told.

Throughout the inhabited world, in all times and under every circumstance, the myths of man have flourished; and they have been the living inspiration of whatever else may have appeared out of the activities of the human body and mind. It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation. Religions, philosophies, arts, the social forms of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries in science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep, boil up from the basic, magic ring of myth. – page 3

So begins Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Joseph Campbell ( 1904-1987 ) believed in the Monomyth as part of what he saw as “the unity of human consciousness and its poetic expression through mythology.”

Campbell begins his work by delving into the human psyche.

For the symbols of mythology are not manufactured; they cannot be ordered, invented, or permanently suppressed. They are spontaneous productions of the psyche, and each bears within it, undamaged, the germ power of its source.

What is the secret of the timeless vision? Fro what profundity of the mind does it derive? Why is mythology everywhere the same, beneath is varieties of costume? And what does it teach?

…

Most remarkable of all, however, are the revelations that have emerged from the mental clinic… In the absence of an effective general mythology, each of us has his private, unrecognized rudimentary, yet secretly potent pantheon of dream. – page 4

He speaks much of Freud, Jung and their followers who record dreams. Many of these dreams are remarkably accurate depictions of mythologies of other cultures to which the dreamer has never been exposed. He gives many examples of such dreams and the parallel mythological stories.

He also writes something that connects with what I thought was a completely unrelated topic: the apparent inability for most young men in America to grow up:

It has always been the prime function of mythology and rite to supply the symbols that carry the human spirit forward, in counteraction to those other constant human fantasies that tend to tie it back. In fact, it may well be that the very high incidence of neuroticism among ourselves follows from the decline among us of such effectual spiritual aid. We remain fixated to the unexorcised images of our infancy, and hence disinclined to the necessary passages of our adulthood. In the United States there is even a pathos of inverted emphasis: the goal is not to grow old, but to remain young; not to mature away from Mother, but to cleave to her. And so, while husbands are worshiping at their boyhood shrines, being the lawyers, merchants, or masterminds their parents wanted them to be, their wives, even after fourteen years of marriage and two fine children produced and raised, are still on the search for love–which can come to them only from the centaurs, sileni, satyrs, and other concupiscent incubi of the rout of Pan, either as in the second of the above recited dreams, or as in our popular, vanilla-frosted temples of the venereal goddess, under the make-up of the latest heroes of the screen. – pages 11-12

He writes about the universal villain:

Wherever he sets his hand there is a cry (if not from the housetops, then–more miserably–within every heart): a cry for the redeeming hero… The hero is the man of self-achieved submission. But submission to what?

…

Only birth can conquer death–the birth, not of the old thing again, but of something new. – page 16

He writes about the power of the reality within our subconscious with this story within us:

If only a portion of that lost totality could be dredged up into the light of day, we should experience a marvelous expansion of our powers, a vivid renewal of life. We should tower in stature. Moreover, if we could dredge up something forgotten not only by ourselves but by our whole generation or our entire civilization, we should become indeed the boon-bringer, the culture hero of the day–a personage of not only local but world historical moment. In a word: the first work of the hero is to retreat from the world scene of secondary effects to those causal zones of the psyche where the difficulties really reside, and there to clarify the difficulties, eradicate them in his own case (i.e., give battle to the nursery demons of his local culture) and break through to the undistorted, direct experience and assimilation of what C.G. Jung has called “the archetypal images” – page 17-18

He quotes

- Jung’s Psychology and Religion from Collected Works, Vol 11

- Ethnische Elementargedankenin der Lehre vom Menchen, Berlin 1895

- Sir James G Frazer’s The Golden Bough :

We need not, with some enquirers in ancient and modern times, suppose that the Western peoples borrowed from the older civilization of the Orient the conception of the Dying and Reviving God, together with the solemn ritual, in which the conception was dramatically set forth before the eyes of the worshippers. More probably the resemblance which may be traced in this respect between the religions of the East and West is no more than what we commonly, though incorrectly, call a fortuitous coincidence, the effect of similar causes acting alike on the similar constitution of the human mind in different countries and under different skies

He writes:

Dream is the personalized myth, myth the depersonalized dream.

The archetype idea is associated with the Stoic concept of the Logoi spermatikoi. (John 1?)

He says he disagrees with a Professor Toynbee, as Toynbee draws the myth back to the Catholic church. No doubt, as Campbell is an atheist. And yet largely because of the atheism of himself and others, he writes that his plight is truly desperate:

It is only those who know neither an inner cal nor an outer doctrine whose plight truly is desperate; that is to say, most of us today, in this labyrinth without and with-in the heart. – page 23

But there’s a solution! Campbell is here to deliver to the secularist a solution to this truly desperate plight:

… we have not even to risk the adventure alone; for the heroes of all time have gone before us; the labyrinth is thoroughly known; we have only to follow the thread of the hero-path. And where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence; where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.

My Response

This book (in this chapter and others) makes a well documented case for the theory that The Hero Story is embedded within the soul of humans near and far, modern and ancient. Campbell says that the universal story is just the outplaying an epic story embedded in the psyche of every human. Now that we have Freud and Jung, we know that’s all it is.

That’s all it is?!

How can one be satisfied with that? It’s a huge answer begging even larger questions. Where did it come from? How did a full and complete hero story get into every human psyche? Who put it there? Does he believe the process of matter and energy through the predestined laws of cause-and-effect put together the human psyche in random order and suddenly the full and complete hero story jumped out?

Campbell’s atheism may have limited his freedom to pursue this, as the presence of a story begs the question of an author.Perhaps Campbell deals with this later or in other writings.

There is one story within every human.

- Does this correspond with Ecclesiastes 3:11 which includes “…He has also set eternity in the hearts of men; yet they cannot fathom what God has done from beginning to end.”

- In a parallel to Campbell’s point about the psyche-engrained myth helping us through stages of life, this line in Ecclesiastes follows the lines that inspired the Byrds “Turn, Turn, Turn” about there being a season for everything.

- Clarke’s commentary says the best translation would read: “Also that eternity hath he placed in their heart, without which man could not find out the work which God hath made from the commencement to the end.” God has deeply rooted the idea of eternity in every human heart; and every considerate man sees, that all the operations of God refer to that endless duration. (my thought: what if he not only placed the idea of eternity in our hearts, but the entire story of eternity?)

- How does this compare with what is proposed by Don Richardson in Eternity in Their Hearts?

- Is the church doing a disservice by not focusing on story, putting Christians in the same truly desperate plight he speaks of for secularists?

- Given that the understanding and living out of the story is, per Campbell, essential to healthy life transitions, what should I do differently for myself, my children, and others I lead?

- Tolkien’s point about Jesus’ story being the best myth – is that true according to the monomyth taught by Campbell?

here is a strange idea abroad that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books. Thus I have found as a tutor in English Literature that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about “isms” and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said. The error is rather an amiable one, for it springs from humility. The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator. The simplest student will be able to understand, if not all, yet a very great deal of what Plato said; but hardly anyone can understand some modern books on Platonism. It has always therefore been one of my main endeavours as a teacher to persuade the young that firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire.

here is a strange idea abroad that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books. Thus I have found as a tutor in English Literature that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about “isms” and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said. The error is rather an amiable one, for it springs from humility. The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator. The simplest student will be able to understand, if not all, yet a very great deal of what Plato said; but hardly anyone can understand some modern books on Platonism. It has always therefore been one of my main endeavours as a teacher to persuade the young that firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire. This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.

This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.