I’ve previously mentioned my men’s book club, “Book Burning” briefly once before. I’ve always tried to alternate between new and old books, based on C.S. Lewis’ advice, though this January things took a turn.

The books selected for a book club are typically books that one or more members have previously read and enjoyed. Because not everyone reads the book before discussion, sometimes the only reading is re-reading by those who already love the book. Alternatively, books can be taken on the recommendation of another. Yet whose recommendation does one take? We aren’t interested in an Oprah book club.

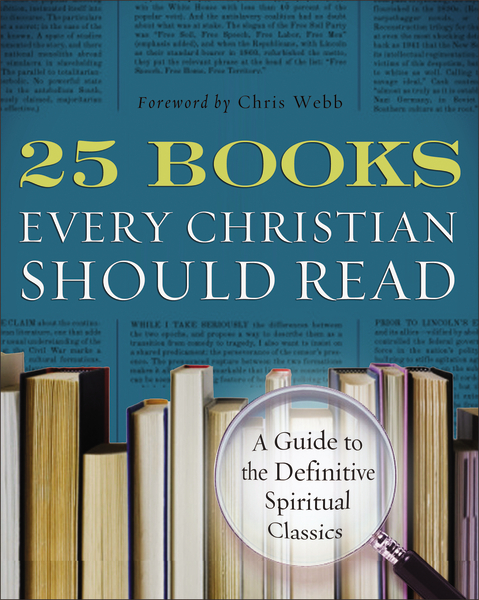

Enter 25 Books Every Christian Should Read by Richard Foster’s Renovaré. Frederica Mathewes-Green was on the board, which lent it a great deal of credibility for us, as her Gender: Men, Women, Sex and Feminism was one of our most discussed books previously read.

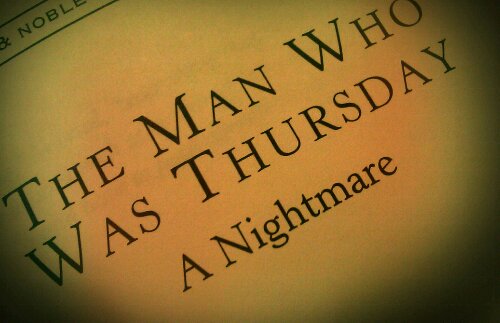

Compiled by a team spanning Orthodox, Catholic, Evangelical and Anabaptist traditions, the chronological list begins with Athanasius’ On the Incarnation and ends with The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri J. M. Nouwen. Books are both fiction and non-fiction, and only books whose authors are now deceased were allowed. This is important as I would have avoided the book had some of the end-of- book recommendations of contemporary books been included in the official list.

I ran the idea of following the 25 Books recommendations by a few guys who are part of Book Burning and we started in January. We’re interspersing other books for a third of our Burnings. I was afraid that reading ancient Christian literature might not draw as many guys, but we’ve had more guys show up for these discussions than we did when we picked books on our own recommendation.

I figured 25 Books Every Christian Should Read would be similar to 10 Books That Screwed Up the World and 5 Others That Didn’t Help, which summarizes the author’s background and book content. What I didn’t realize – but now very much appreciate – is that 25 Books is structured as a guide for discussing the book with others. It’s perfect as a guide for Book Burning.

It also allowed me to add new direction and purpose to the book club. It’s still about hanging out with friends, eating, maybe smoking a pipe, and discussing books; it’s now also about spiritual transformation. Thanks to the books we’ve read, I see my faith and life differently now.

Since January I’ve begun to forget some of my take-aways from and responses to the books. I plan on writing up, briefly, my thoughts and bits from our discussion about these 25 books so I don’t permanently forget them.

here is a strange idea abroad that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books. Thus I have found as a tutor in English Literature that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about “isms” and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said. The error is rather an amiable one, for it springs from humility. The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator. The simplest student will be able to understand, if not all, yet a very great deal of what Plato said; but hardly anyone can understand some modern books on Platonism. It has always therefore been one of my main endeavours as a teacher to persuade the young that firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire.

here is a strange idea abroad that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books. Thus I have found as a tutor in English Literature that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about “isms” and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said. The error is rather an amiable one, for it springs from humility. The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator. The simplest student will be able to understand, if not all, yet a very great deal of what Plato said; but hardly anyone can understand some modern books on Platonism. It has always therefore been one of my main endeavours as a teacher to persuade the young that firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire. This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.

This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.

Rob Bell, pastor, author, and speaker in the popular Nooma video series, has just published a book called “Love Wins.” The book is a challenge to Christians to re-think our views of hell, heaven, and salvation.

Rob Bell, pastor, author, and speaker in the popular Nooma video series, has just published a book called “Love Wins.” The book is a challenge to Christians to re-think our views of hell, heaven, and salvation. The idea communicated to me so far that we all experience “hell” every day on earth is packed so full of presuppositions – it presumes that “hell” is simply synonymous for “thinks I don’t like” or “things I think are awful.”

The idea communicated to me so far that we all experience “hell” every day on earth is packed so full of presuppositions – it presumes that “hell” is simply synonymous for “thinks I don’t like” or “things I think are awful.”